Overall, 40 pts were included for

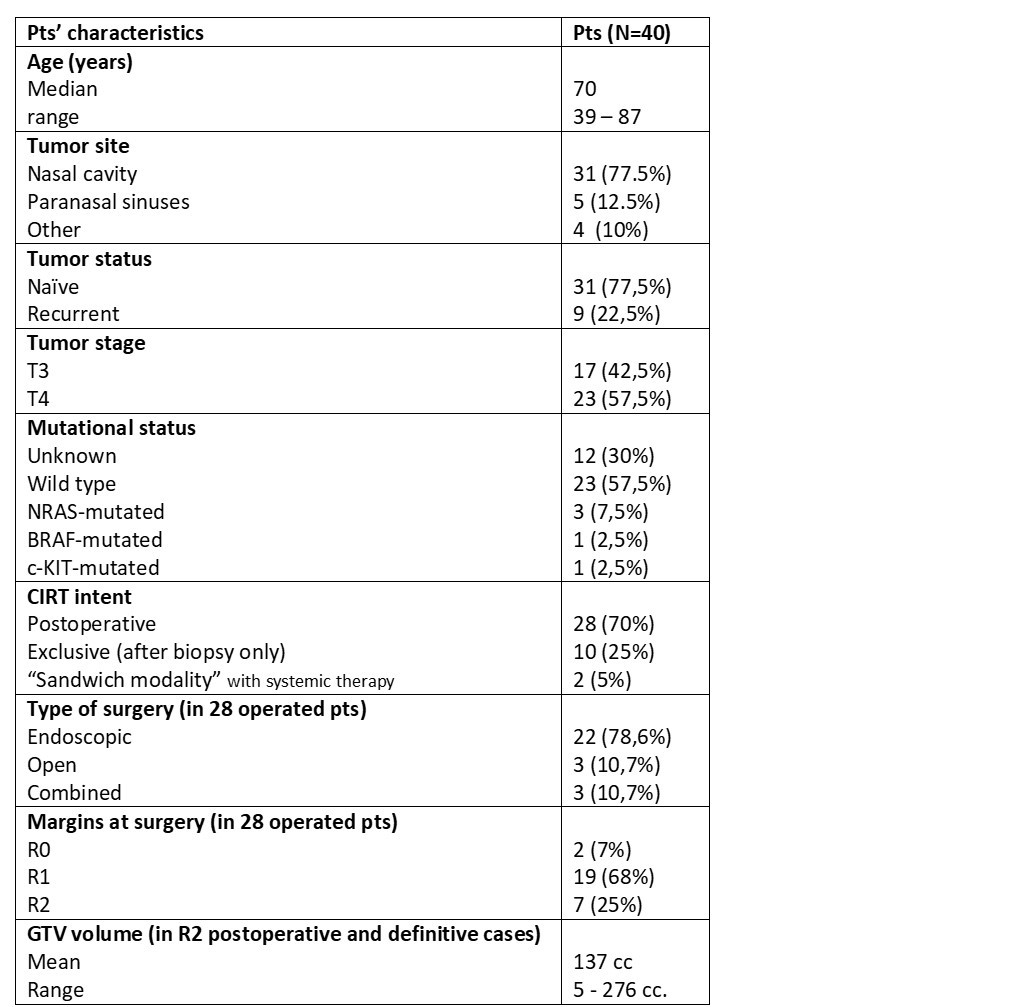

analysis. Table 1 shows pts’ characteristics.

Twenty-eight (70%) pts were

treated after surgery, 10 (25%) with exclusive CIRT, 2 (5%) pts received

systemic therapy before and after CIRT (chemotherapy in one case, immunotherapy

in the other).

CIRT treatment schedules were given

in 16 fractions (4 fr/week) for a total dose of 65.6 RBE Gy and 68.8 RBE Gy in

22(55%) and 18(45%) pts, respectively. Moreover, 18 pts (44%) received

immunotherapy after CIRT as part of the treatment for the primary tumor or at

the relapse.

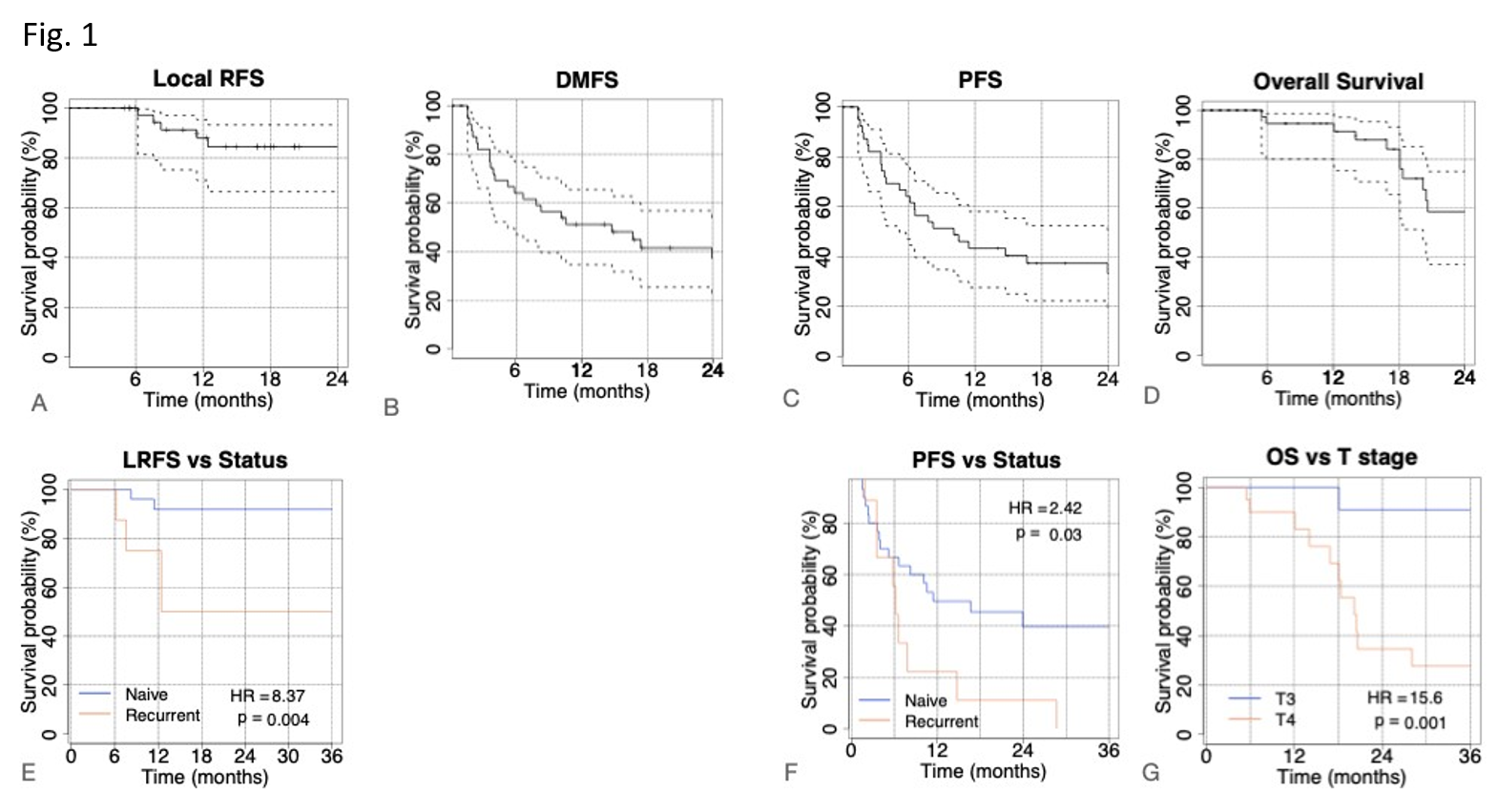

Median follow-up (FU) time was 18 mo

(range 5-81 mo). Two-years- LRFS, PFS, DMFS and and OS were 84.5%, 33.2%, 37.3%

and 58.6% respectively (see first row in Fig1). No difference in clinical

outcome was found for resected compared to unresected patients. Naïve tumor

status was associated with better LRFS (HR=8.4 and p-value<0.01, Fig1 E) and

PFS (HR=2.4 and p=0.03, Fig1 F). Better OS was reported for T3 stage (HR=15.6,

p= 0.001, Fig 1G) and age years using a univariate cox regression model. These

variables were considered in a bivariate model. HR was 4.3 (p<0.01) for T4

and 3.9 (p=0.03) for age years, with an AUC=0.81.

To analyse the relationship between

immunotherapy and CIRT we found that combined treatment after CIRT in T4 stages

was associated with better OS outcome at 30 months (40%) than patients not

receiving immunotherapy (20%). In patients not receiving immunotherapy after

CIRT, T3 and T4 stages maintained significant differences in 3y-OS (100% vs

19.2%), whereas T3 and T4 patients receiving immunotherapy reached similar OS

rates (71.4% vs 72.7%).

As far as concerned side effects, acute tox at

the end of CIRT was G1-G2 in 95% and G3 in 5% of pts. Late tox was G0 in 10%

and G1-G2 in 81% of pts; late toxicity ≥ G3 consisted in one G3 unilateral hear

impairment and 2 unilateral visual loss of grade G3 and G4, respectively

(expected tox).