In memory of Professor Sir Michael Peckham, 1935-2021 - PDF Version

.jpg.aspx)

Dear colleagues and friends,

It is with great sadness that we have to inform you that Professor Sir Michael Peckham, FMedSci, FRCP, FRCS, FRCR, FRCPath, died of lymphoma on 13 August 2021 aged 86 years. He was a visionary oncologist and polymath whose talents extended way beyond clinical academic medicine to health service research and policy. He was also a very accomplished and well-known artist. He co-founded the European SocieTy for Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO) in 1981. He is survived by his wife Catherine, three sons and nine grandchildren.

Michael Peckham was born in the small Welsh village of Panteg in 1935. He won a scholarship from Monmouth Grammar School to study natural sciences at St Catharine’s College, Cambridge, and then trained in medicine at University College London. He met Catherine, who was also a student, at university and they married in 1958 during his final year of studies. His interest was always divided between medicine and art; his first solo art exhibition was held in 1964.

He was awarded a prestigious UK Medical Research Council fellowship to study at the Department of Radiation Therapy at the Institut Gustave Roussy, in Paris, working under Professor Maurice Tubiana. His interest developed in lymphoma and leukaemia during exciting times for these subjects with the advent of bone marrow transplantation and curative radiation techniques for Hodgkin’s disease. In his article in Perspectives: the art of medicine entitled ‘Art and oncology: one life’ (The Lancet, 2018), he described the pull of rival “laboratories” in the two worlds of cell biology and Stanley Hayter’s artists’ studio in Montparnasse. He was considerably influenced by Tubiana’s sophisticated approach to radiation therapy, which was based on an alliance between clinical medicine, physics and radiobiology.

Peckham returned to London in 1967 to work at the Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) and at the Royal Marsden Hospital (RMH). In 1973 he was awarded the Chair of Radiotherapy at the ICR. Over the next 12 years he continued his work in Hodgkin’s lymphoma. He developed the scientific rationale and clinical evidence for mantle-field radiation and tested a combination chemotherapy that comprised chlorambucil, vinblastine, procarbazine and prednisolone (CHlVPP), which could be applied instead of the higher toxicity combination therapy that involved mechlorethamine hydrochloride, vincristine sulphate, procarbazine hydrochloride and prednisolone, known as MOPP. Both became new standards of care at the time in the UK. However, his major influence was in the dramatic revolution that was taking place in testicular cancer treatment with the advent of platinum-based combination chemotherapy. With Alan Horwich, his senior lecturer and successor, he introduced etoposide to replace vinblastine to produce the bleomycin, etoposide, platinum (BEP) schedule, which showed reduced toxicity. He also explored the role of the ICR’s recently synthesised platinum-based complex carboplatin. Carboplatin was evaluated in non-seminomatous germ cell tumours and in seminoma, and continues to be valuable both as adjuvant monotherapy and as a component of intensive induction and high-dose therapy schedules. He oversaw a paradigm change with the policy of surveillance for Stage 1 disease, as he appreciated that treatment (retroperitoneal lymph node dissection or “dog-leg” radiotherapy) might be avoided in many men and early recurrences could be salvaged with chemotherapy +/- surgery.

He was a highly regarded and empathetic clinician. His ward rounds and clinics were illuminated by pictures of Peckham man as he documented sites of disease and responses to treatment. Initially hand drawn in patient notes, these were developed into A3-sized printed charts and used routinely for all men. They were meticulously updated by the team at the Bob Champion data unit. The different visual patterns that were seen on CT scans were developed into the RMH staging system and 35 of the drawings were shown at the Royal Academy in 2004 under the title Treatments. The English jump jockey Bob Champion became one of the unit’s most well-known survivors. Diagnosed in 1979, he recovered after intensive chemotherapy and went on to win the Grand National steeplechase on the horse Aldaniti in 1981 ‑ one of sporting history’s greatest come-backs. Together, Champion and Peckham established the Bob Champion Cancer Trust, which funded testicular cancer research at first and now prostate cancer research. I have the privilege of continuing the link as the Trust’s scientific advisor.

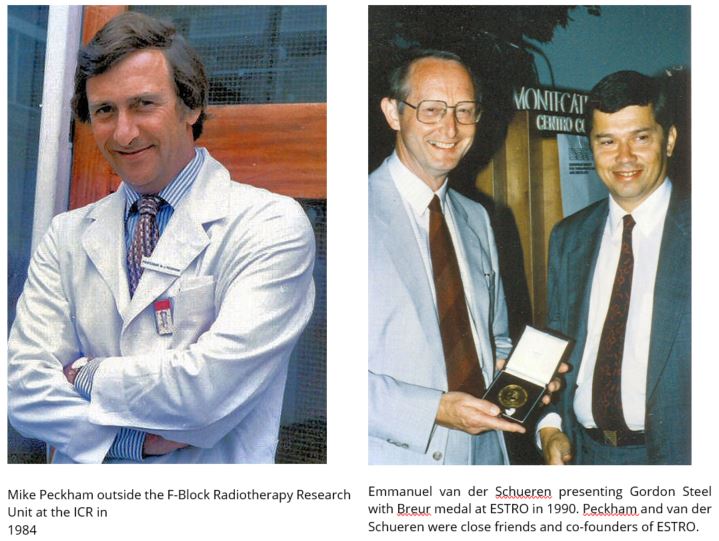

Shortly after arriving at the RMH, Peckham realised the value of underpinning clinical research and training with laboratory studies. At that time Gordon Steel was head of the Biophysics Unit of the ICR. On Peckham’s initiative, this team was incorporated into the Radiotherapy Section of the ICR and renamed the Radiotherapy Research Unit. The emphasis of radiobiology research then became more focused on clinical objectives, and over the next 25 years around 30 junior oncologists spent time in F-Block working for MD or PhD research degrees. Many of them went on to occupy senior clinical and academic positions in the UK and abroad.

Peckham was a believer in ‘team science’ before the term was popular and strongly pro-European. He led the way in the establishment of international cross-disciplinary academic groups and apart from co-founding ESTRO in 1981, he helped to set up the European School of Oncology (ESO) in 1982 and was founder and first chairman of the Federation of European Cancer Societies (FECS), now the European Cancer Organisation. The formation of the FECS represented a significant milestone in shifting cancer medicine towards a multidisciplinary approach, bringing radiation oncologists (ESTRO) together with medical oncologists (through the European Society for Medical Oncology), cancer surgeons (through the European Society of Surgical Oncology), and laboratory cancer researchers (through the European Association for Cancer Research). He strongly believed in the application of evidence-based medicine. In 1986 he moved from the ICR/RMH to become the director of the British Postgraduate Medical Federation, which brought together seven London postgraduate medical institutes. Additionally he was vice-chair of the Imperial Cancer Research Fund (now Cancer Research UK) from 1986 to 1991. In 1991 he became the first National Health Service director of research and development. He had a clear view that NHS decision-making and the formulation of health policy should be based on reliable information from research. Through the programme he facilitated funding for the Cochrane Centre for systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials across all aspects of healthcare and laid the foundations for the National Institute for Clinical Excellence, which later became the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

Peckham continued to focus on big-picture policy areas for the rest of his career. He was director of the School of Public Policy at University College London between 1997 and 2000, and chair of the UK’s National Educational Research Forum, established in 2000. He supported ‘blue-sky’ thinking and in 2000 chaired the foresight panel "Healthcare in 2020" for the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, Office of Science and Technology. He received his knighthood for services to medicine in 1995.

.jpg.aspx)

From the clinic to art: Peckham man from clinical charts showing, on left: RMH Stage IVC L2 H+ mixed germ cell tumour treated by BEP chemotherapy, and on right: Elements of Renewal 1 2004

After his retirement, Peckham devoted time to his art, mounting a series of one-person exhibitions. In the last two years he published two books of his paintings, one of which was completed during lockdown. Much of the imagery in Balance of the Interior drew on his experiences as a cancer physician and artist. Peckham had the wonderful talent, energy and motivation to affect the outcomes for so many individual patients and to reflect his medical journey though the imagery in his paintings. He was one of our leading figures in oncology during the past 50 years. We mourn his passing but celebrate his great humanity and many achievements.

David Dearnaley, MA, MD, FRCP, FRCR

Emeritus Professor of Uro-oncology

The Institute of Cancer Research &

Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust

London, UK

Gordon Steel DSc

Emeritus Professor of Radiobiology

The Institute of Cancer Research

London, UK